The Secret Sauce of Smart Search: Exploring AI Algorithms

Why AI Search Algorithms Are the Brain Behind Every Smart Decision

AI search algorithms are the fundamental decision-making systems that power everything from your GPS finding the fastest route home to game characters navigating complex worlds. At their core, these algorithms explore possible solutions to find the best path from a starting point to a goal, whether that is a physical location, a puzzle solution, or an optimal business decision.

Quick Answer: What You Need to Know About AI Search Algorithms

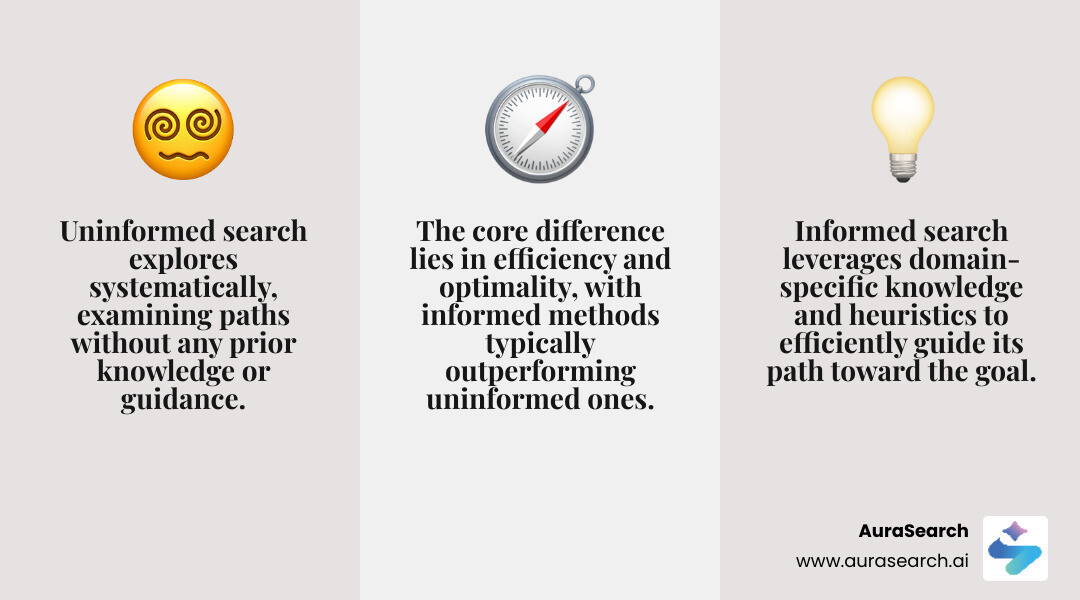

- Uninformed (Blind) Search : Explores systematically without any guidance, like searching a maze without a map

- Informed (Heuristic) Search : Uses domain knowledge to guide the search more efficiently, like having a compass pointing toward your goal

- Key Algorithms : BFS (explores level-by-level), DFS (goes deep first), A* (combines path cost and heuristic estimates)

- Performance Metrics : Completeness (finds a solution), optimality (finds the best solution), time/space complexity

If you are a marketer seeing your organic traffic slip or struggling to show up in ChatGPT and AI Overviews, understanding these algorithms is not just academic, it is practical. The same principles that help robots steer around obstacles are now shaping how AI decides which content to cite and recommend.

Search algorithms are undergoing a major shift. While traditional SEO focused on ranking in a list of blue links, today's AI-powered search synthesizes answers from multiple sources. Nearly 40% of Gen Z now turns to TikTok over Google for some queries, and Gartner predicts that by 2026, 50% of all searches will be influenced by AI tools.

The shift is not only about where people search, it is about how AI finds and prioritizes information. The algorithms that once helped solve puzzles and plan robot movements are now deciding which businesses get cited in AI-generated answers.

This guide breaks down the core AI search algorithms in simple terms, showing you how they work, why they matter, and what this evolution means for staying visible in an AI-first search landscape.

Simple AI search algorithm word guide:

The Foundations: Evaluating Search Performance

Before diving into specific algorithms, it is crucial to understand how we measure their effectiveness. Just like a good chef evaluates ingredients, we need criteria to assess how well an AI search algorithm performs. These criteria help us choose the right tool for the job, balancing the desire for a perfect solution with the reality of limited resources.

The key criteria used to evaluate the performance of AI search algorithms are:

- Completeness: Does the algorithm guarantee to find a solution if one exists? For some problems, finding any solution is a victory.

- Optimality: Does the algorithm guarantee to find the best (for example, shortest or cheapest) solution? Sometimes, an adequate solution is fine, but in other cases only the absolute best will do.

- Time Complexity: How long does the algorithm take to find a solution? This is often expressed in terms of the branching factor (b), which is the average number of choices at each state, and the solution depth (d), the length of the shortest path to the goal.

- Space Complexity: How much memory does the algorithm require to perform the search? This can be a critical factor, especially for large problem spaces.

We also consider the path cost , which is the cumulative cost of actions taken from the initial state to the current state. This is especially important for algorithms aiming for optimal solutions.

Here is a quick comparison of some major search algorithms based on these criteria:

| Algorithm | Complete? | Optimal? (Uniform Cost) | Time Complexity (Worst Case) | Space Complexity (Worst Case) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breadth-First Search | Yes | Yes | O(b^d) | O(b^(d+1)) |

| Depth-First Search | No | No | O(b^m) | O(bm) |

| Uniform Cost Search | Yes | Yes | O(b^(1+C*/ε)) | O(b^(1+C*/ε)) |

| Iterative Deepening DFS | Yes | Yes | O(b^d) | O(bd) |

| Greedy Best-First Search | No | No | O(b^m) | O(b^m) |

| A* Search | Yes | Yes (Admissible H) | O(b^d) | O(b^d) |

(Note: b is the branching factor, d is the depth of the shallowest goal, m is the maximum depth of the search space, C is the optimal path cost, and ε is the minimum edge cost.)*

What Makes a Good Search Strategy?

A good search strategy is one that efficiently finds a solution, and ideally the best solution, given the constraints of the problem. This means balancing the desire for completeness and optimality with practical considerations like execution time and memory usage. For example, in a chess game, finding the best move is critical, even if it takes a bit longer. For a robot navigating a known factory floor, a good enough path might be sufficient if it is found very quickly. The choice of strategy always depends on the specific problem and its requirements.

Uninformed Search: Exploring Without a Map

Imagine you are trying to find your way out of a dark, unfamiliar forest without a map or any idea which direction leads to safety. That is essentially what uninformed search algorithms do. They explore the problem space systematically, without any domain-specific knowledge or hints about where the goal might be. They are often called blind search algorithms because they operate without foresight, treating all nodes in the search space equally. These approaches are often considered brute-force search methods.

The problem space is represented as a state space graph, where nodes are states (snapshots of the problem) and edges are actions (transitions between states). We start from an initial state and aim to reach a goal state.

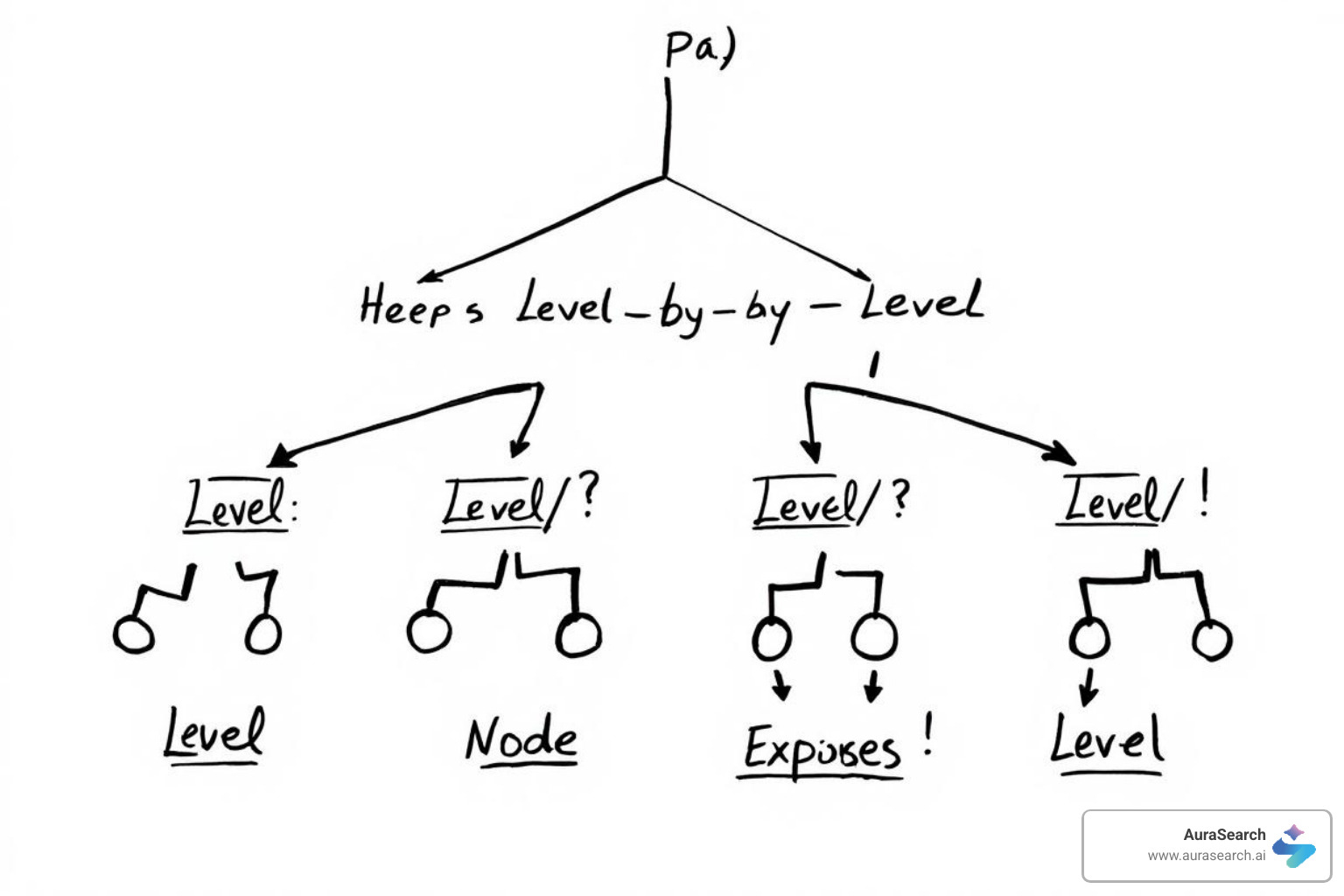

Breadth-First Search (BFS)

Breadth-First Search (BFS) is like exploring the forest by systematically checking every path one step away, then every path two steps away, and so on. It expands all nodes at the current depth level before moving on to nodes at the next depth level. It uses a First-In, First-Out (FIFO) queue to manage the nodes to be explored, ensuring a level-by-level traversal.

- Strengths: BFS is complete (it will always find a solution if one exists) and optimal (it finds the shortest path in terms of the number of steps, assuming uniform step costs).

- Weaknesses: Its primary drawback is its high space and time complexity. In the worst case, BFS has a time complexity of O(b^d) and a space complexity of O(b^(d+1)), where b is the branching factor and d is the depth of the shallowest goal. This means it can quickly consume a lot of memory, especially in large search spaces.

Depth-First Search (DFS) and Its Variations

Depth-First Search (DFS) takes a different approach. Instead of exploring broadly, it plunges deep into one path as far as possible before backtracking. Think of it as following one trail in the forest until you hit a dead end, then returning to the last fork and trying another trail. DFS typically uses a Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) stack (often implemented recursively) to keep track of nodes to visit.

- Strengths: DFS has excellent space efficiency, with a space complexity of O(bd), making it suitable for problems with deep solutions or limited memory.

- Weaknesses: It is not complete (it might get stuck in an infinite loop if the search space has cycles or infinitely deep paths) and not optimal (it might find a very long path to the goal, even if a shorter one exists).

To address DFS limitations, we have variations:

- Depth-Limited Search (DLS): This is DFS with a predetermined depth limit (L). If the search reaches this limit without finding a solution, it backtracks. This prevents infinite loops but sacrifices completeness if the solution lies beyond L.

- Iterative Deepening Search (IDS) / Iterative Deepening Depth-First Search (IDDFS): This variation combines the main benefits of BFS and DFS. It performs DLS repeatedly, increasing the depth limit (L) by one each time (L = 0, L = 1, L = 2, and so on). It is like checking paths one step deep, then two steps deep, and so on, but using DFS memory efficiency at each stage. IDDFS is complete, optimal (for uniform step costs), and has a space complexity of O(bd), making it often the preferred uninformed search method when memory is a concern.

Uniform-Cost Search (UCS)

Sometimes the cost of moving from one state to another is not uniform; some paths are more expensive than others. Uniform-Cost Search (UCS) is designed for such scenarios. It is like finding the cheapest route through a city where different roads have different tolls or traffic. UCS expands the node with the lowest cumulative path cost g(n) from the start node. It uses a priority queue to always explore the cheapest path first.

- Strengths: UCS is complete and optimal even with varying edge costs, as it always expands the node that has been reached by the cheapest path so far.

- Weaknesses: It can be inefficient if the costs are similar or if there are many paths with costs less than the optimal path, potentially exploring a large number of nodes. Its time and space complexities are similar to BFS in the worst case, O(b^(1 + C /ε)), where C is the optimal path cost and ε is the minimum edge cost.

Informed Search: The Power of Heuristics

While uninformed search algorithms are like exploring blindly, informed search algorithms are equipped with a compass, a heuristic function, that guides them toward the goal. They use domain-specific knowledge to estimate how close a given state is to the goal, making the search far more efficient, especially in large and complex problem spaces. This is where the real intelligence in AI search algorithm design begins to appear.

More info about optimizing for AI search

The Role of a Heuristic Function in an AI search algorithm

A heuristic function, denoted as h(n), is essentially a rule of thumb that estimates the cost from the current state n to the goal state. It does not guarantee the exact cost, but it provides a useful guess, helping the algorithm prioritize which paths to explore. You can think of it as a mental shortcut.

For an AI search algorithm to be effective, its heuristic function needs certain properties:

- Admissible Heuristic: An admissible heuristic never overestimates the true cost to reach the goal. If the true cost from node n to the goal is h (n), then an admissible heuristic h(n) must satisfy h(n) ≤ h (n). This property is crucial for algorithms like A* to guarantee optimality. For example, in pathfinding, the straight-line distance (Euclidean distance) to the goal is an admissible heuristic because you cannot get there faster than a straight line.

- Consistent Heuristic: A consistent heuristic is a slightly stronger condition. It satisfies h(n) ≤ cost(n, n') + h(n') for every node n and every successor n' of n, where cost(n, n') is the actual cost of moving from n to n'. This is also known as the triangle inequality. A consistent heuristic is always admissible, but an admissible one is not necessarily consistent. Consistency helps prevent algorithms from repeatedly expanding already visited nodes.

The choice and quality of the heuristic function dramatically impact the performance of informed search algorithms. A good heuristic can significantly reduce the number of nodes an algorithm needs to explore, making it much faster. Conversely, a poor heuristic can lead the search astray, making it no better than uninformed search, or even worse.

Greedy Best-First Search

Greedy Best-First Search is the most straightforward application of a heuristic. It always expands the node that appears to be closest to the goal, according to its heuristic function h(n). Its evaluation function is simply f(n) = h(n). It is like always heading towards the tallest visible mountain, hoping it is the fastest way to the summit.

- Strengths: It can be very fast, as it aggressively moves toward what it perceives as the goal.

- Weaknesses: Because it only considers the estimated cost to the goal and ignores the cost already incurred g(n), it is neither optimal nor complete. It is prone to getting stuck in local optima, meaning it might find a path that looks good locally but is not the best overall, or it might get stuck going down a path that never reaches the goal.

A* Search: The Gold Standard

A* Search, often pronounced A-star, is widely considered the most popular and effective AI search algorithm for pathfinding and graph traversal. It combines the strengths of Uniform-Cost Search and Greedy Best-First Search. A* evaluates each node n using an evaluation function f(n) = g(n) + h(n). Here, g(n) is the actual cost from the start node to n, and h(n) is our heuristic estimate of the cost from n to the goal. This balance ensures that A* finds the shortest path while also being guided efficiently toward the goal.

A* was first published in 1968 by Peter Hart, Nils Nilsson, and Bertram Raphael, and its foundational work, " A Formal Basis for the Heuristic Determination of Minimum Cost Paths ", remains a cornerstone in AI.

- Conditions for Optimality: A* is guaranteed to be complete (it will always find a solution if one exists on finite graphs with non-negative edge weights) and optimal (it guarantees the least-cost solution) when using an admissible heuristic. If the heuristic is also consistent, A* will expand the fewest possible nodes to find the optimal path among all algorithms that extend search paths from the root.

- Strengths: Its combination of completeness, optimality, and efficiency makes it a common choice for many pathfinding problems.

- Weaknesses: The primary drawback of A* is its space complexity, which is O(b^d) in the worst case. It stores all generated nodes in memory, which can be restrictive for very large graphs.

Local Search: Hill Climbing

Unlike other informed search methods that explore a graph or tree, local search algorithms operate on a single current state and iteratively move to a neighboring state that improves the objective function. Hill Climbing is a prime example. Imagine being dropped somewhere on a mountain and trying to reach the highest peak (the global optimum) by always taking a step that leads uphill.

- Mechanism: It starts with a prospective solution and repeatedly makes small changes to it, moving to a better neighboring solution if one exists. This process continues until no further improvements can be made.

- Strengths: Hill Climbing uses very little memory, typically only storing the current state and its neighbors. It can find reasonable solutions in large or infinite state spaces where systematic algorithms are unsuitable, and it can return a valid solution even if interrupted.

- Weaknesses:

Its main limitations are that it is neither complete nor optimal. It is highly susceptible to getting stuck in:

- Local maxima: A peak that is higher than its immediate neighbors but not the highest point on the entire landscape.

- Plateaus: A flat area where all neighboring states have the same value, making it impossible to move further uphill.

- Ridges: A sequence of local maxima that form a ridge, which can be difficult to traverse by only considering immediate neighbors.

This makes Hill Climbing more suitable for optimization problems where finding a good solution is enough, rather than guaranteeing the absolute best.

The AI Search Algorithm in the Real World

The theoretical structure of AI search algorithms translates into tangible benefits across countless real-world applications. These algorithms are the often unseen systems behind many of the smart tools we interact with daily, but they also come with their own set of challenges.

Practical Applications of Search Algorithms

- Pathfinding in Video Games: From non-player characters navigating complex game environments to finding the shortest route for a player character, A* search is a common algorithm of choice. It helps game AI efficiently chase players, find objectives, and avoid obstacles.

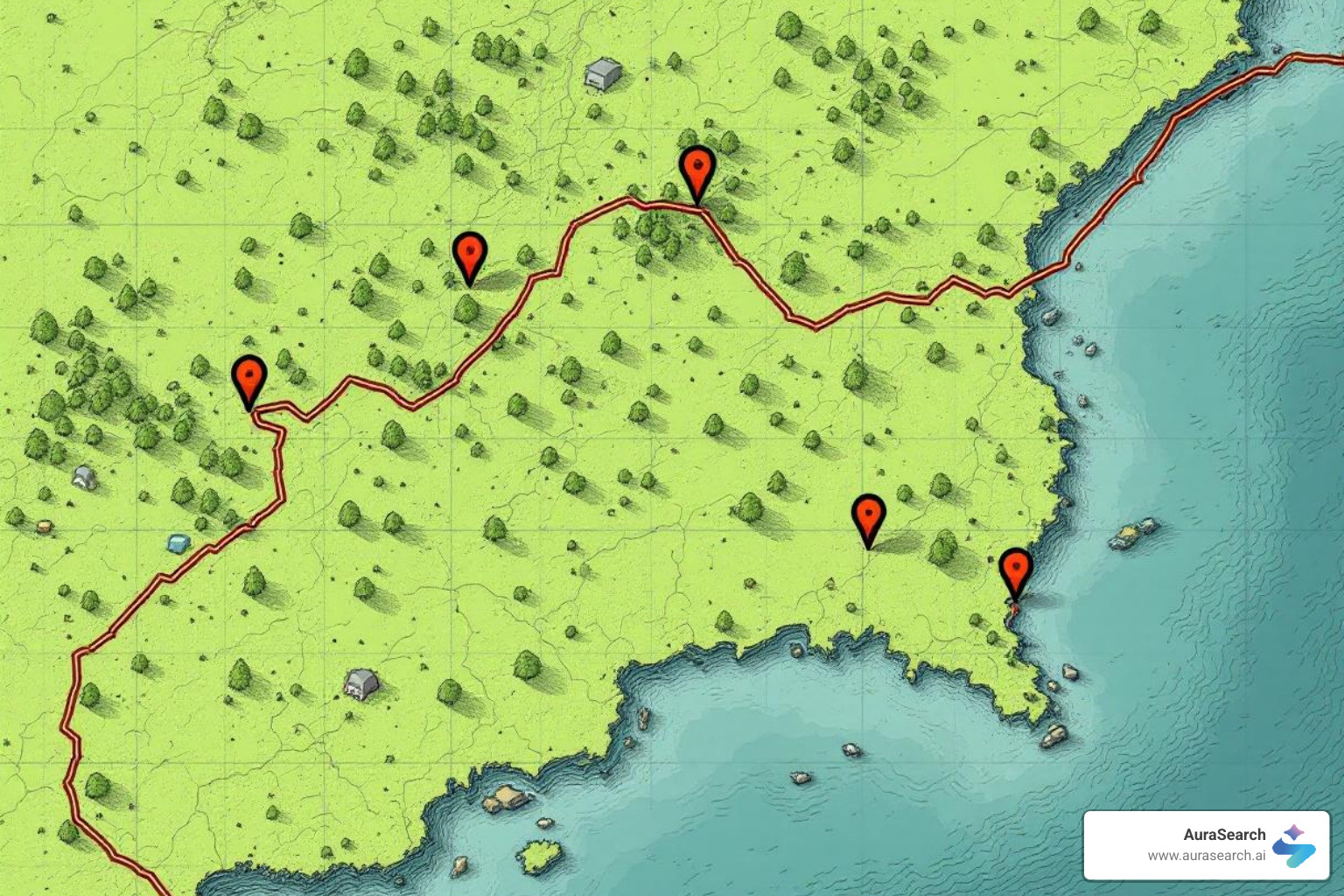

- GPS Navigation and Route Planning: When your GPS suggests the fastest route or shortest distance, it is likely employing variations of A* or Dijkstra's algorithm. These systems analyze road networks (graphs) to find optimal paths, considering factors like distance, traffic, and speed limits.

- Robotics and Motion Planning: Robots need to find collision-free paths through dynamic environments. Search algorithms help them plan movements, avoid obstacles, and reach target locations, whether it is a warehouse robot or a Mars rover analyzing data and navigating terrain.

- Network Routing: In computer networks, algorithms like UCS (or its variants) are used to find the most efficient routes for data packets, minimizing latency or cost.

- Puzzles and Games: Early AI research heavily used search algorithms to solve classic puzzles like the 8-puzzle or Rubik's Cube, and for playing strategy games like chess or checkers. DFS, BFS, and more advanced algorithms like Monte Carlo Tree Search are important here.

- Planning and Scheduling: In logistics, project management, and resource allocation, search algorithms help create efficient plans and schedules, optimizing for time, cost, or resource utilization.

As we move Beyond Keywords: Optimising Content for the AI Search Era , these principles of efficient pathfinding and decision-making are increasingly relevant to how AI finds and delivers information.

Challenges and the Future of AI Search

Despite their power, AI search algorithms face significant challenges, especially as problems become larger and more complex:

- Computational Complexity: For many real-world problems, the search space can be extremely large. Even with a good heuristic, the worst-case complexity for many algorithms remains exponential, making them computationally expensive.

- Memory Constraints: Algorithms like BFS and A* require storing many nodes in memory, which can quickly become a bottleneck for extensive graphs. This is why memory-bounded variants like Iterative Deepening A* (IDA*) are often explored.

- Heuristic Accuracy: The effectiveness of informed search depends heavily on the quality of its heuristic function. Designing an accurate, admissible, and consistent heuristic for complex, novel problems is a significant challenge. A poorly chosen heuristic can lead to inefficient or incorrect solutions.

- Scalability: Adapting these algorithms to handle massive datasets, such as those found in web search or large-scale recommendation systems, requires advanced techniques and distributed computing.

The future of AI search algorithm development is changing quickly. There is a rise in machine learning techniques being used to develop or improve heuristic functions, replacing hand-crafted rules with learned models. This allows AI systems to adapt and find better search strategies over time. Moreover, the emergence of generative AI and large language models (LLMs) is redefining search entirely. Instead of simply finding links, AI is now synthesizing information to provide direct answers. This shift necessitates new strategies for AI Overview Optimisation , focusing on how content can be structured and presented to be easily consumed and cited by these advanced AI systems.

Frequently Asked Questions about AI Search Algorithms

What is the most widely used search algorithm?

A* Search is widely regarded as one of the most used and effective AI search algorithm approaches. Its popularity comes from its balance of efficiency and accuracy. It consistently finds optimal paths (the best solutions) when provided with an admissible heuristic, and it typically does so more quickly than many uninformed methods. This makes it a common choice for applications ranging from video game pathfinding to route planners.

Why are search algorithms fundamental to AI?

Search algorithms are fundamental to AI because they provide a structured framework for problem-solving. Many AI tasks, such as pathfinding, optimization, planning, and decision-making, can be formulated as searching through a space of possible states to find a goal state. They enable AI systems to explore possibilities, evaluate choices, and ultimately act in a way that appears intelligent, making them a core element behind many AI applications.

Which search algorithm is the fastest?

The fastest AI search algorithm depends heavily on the specific problem and the available information. Greedy Best-First Search can often be faster than A* because it aggressively pursues the goal using only its heuristic estimate, potentially cutting short the search. However, this speed comes at a cost: Greedy Best-First Search is not guaranteed to find the optimal solution and can easily be misled by poor heuristics. A*, while sometimes slightly slower than a pure greedy approach, guarantees optimality with the right heuristic, making it a strong and efficient choice when both speed and the best solution are required.

Conclusion

We have explored the core ideas behind AI search algorithms , from the blind, systematic explorations of uninformed methods like BFS, DFS, and UCS, to the guided, intelligent searches powered by heuristics in algorithms like Greedy Best-First Search and A*. These algorithms are the backbone of countless AI applications, enabling everything from efficient navigation to intelligent game playing.

Understanding the strengths, weaknesses, and appropriate use cases for each AI search algorithm is crucial for developing effective AI systems. A* stands out as a powerful, balanced algorithm, but the continuous evolution of AI, particularly with generative models, demands ongoing adaptation.

As search evolves with generative AI, traditional SEO strategies are being rewritten. Businesses need expert guidance to ensure their content is not just ranked, but also actively cited and referenced by AI systems. AuraSearch helps companies adapt their strategies for this new frontier, ensuring they remain visible and authoritative in the AI-first search landscape.